Rethinking Cryptoeconomics - Part 4: A Post-Capitalist Critique of “Maximal Extractable Value”

Navigating the New Frontier: Tipping the Scales of MEV Dynamics in favour Decentalized Autonomous Societies

In 2021, the Flashbots team shed light on a concerning trend in the blockchain space—the exploitation of “Maximal Extractable Value” (MEV*). Since the Ethereum network transitioned from Proof-of-Work to Proof-of-Stake in September 2022, MEV has been responsible for the extraction of more than 400,000 ETH from the Ethereum network. This phenomenon, driven by practices like frontrunning and arbitrage, underscores the challenges posed by self-interest and profit maximization in decentralized systems.

The current trajectory of MEV poses existential risks to the original vision of creating decentralized and equitable systems. Where properties such as censorship resistance and transparency once defined the Ethereum blockchain, today low-level transaction censorship and opaque MEV strategies threaten the protocol. There is an urgent need to steer the development of blockchain protocols and applications towards prioritizing common good over individual profit.

As earlier segments in this post-capitalist cryptoeconomics series have argued, this intervention should involve a reevaluation of existing incentive structures, governance models, and the overarching principles guiding the development of decentralized technologies. Emphasizing transparency, fairness, and environmental sustainability -- values that are aligned with many of crypto evangelists today -- becomes paramount to ensure the long-term viability and positive impact of these technologies.

Understanding MEV: Illuminating the Dark Forest

MEV refers to the profit miners or validators can make by strategically ordering, including, or excluding transactions within a block. This practice capitalizes on the information asymmetry between ordinary users and those with privileged access or capabilities within the network. While MEV occurs in multiple layers of the Web 3 stack, the problem of MEV has deep roots in the protocol layer, in the memory pool, or what is widely referred to as the “mempool”.

In the blockchain context, a mempool is a critical component where transactions wait before being confirmed by network miners or validators. It's akin to a holding area for unconfirmed transactions, each vying for inclusion in the next block. Within this space, various actors can view and select transactions, setting the stage for Maximum Extractable Value.

Problems occurring at the mempool level have risen over the past few years. In the seminal essay, Ethereum as a Dark Forest, the authors describe the mempool space as an extremely treacherous zone.

It’s no secret that the Ethereum blockchain is a highly adversarial environment. If a smart contract can be exploited for profit, it eventually will be. The frequency of new hacks indicates that some very smart people spend a lot of time examining contracts for vulnerabilities.

But this unforgiving environment pales in comparison to the mempool (the set of pending, unconfirmed transactions). If the chain itself is a battleground, the mempool is something worse: a dark forest.

…

In the Ethereum mempool … apex predators take the form of “arbitrage bots.” Arbitrage bots monitor pending transactions and attempt to exploit profitable opportunities created by them.

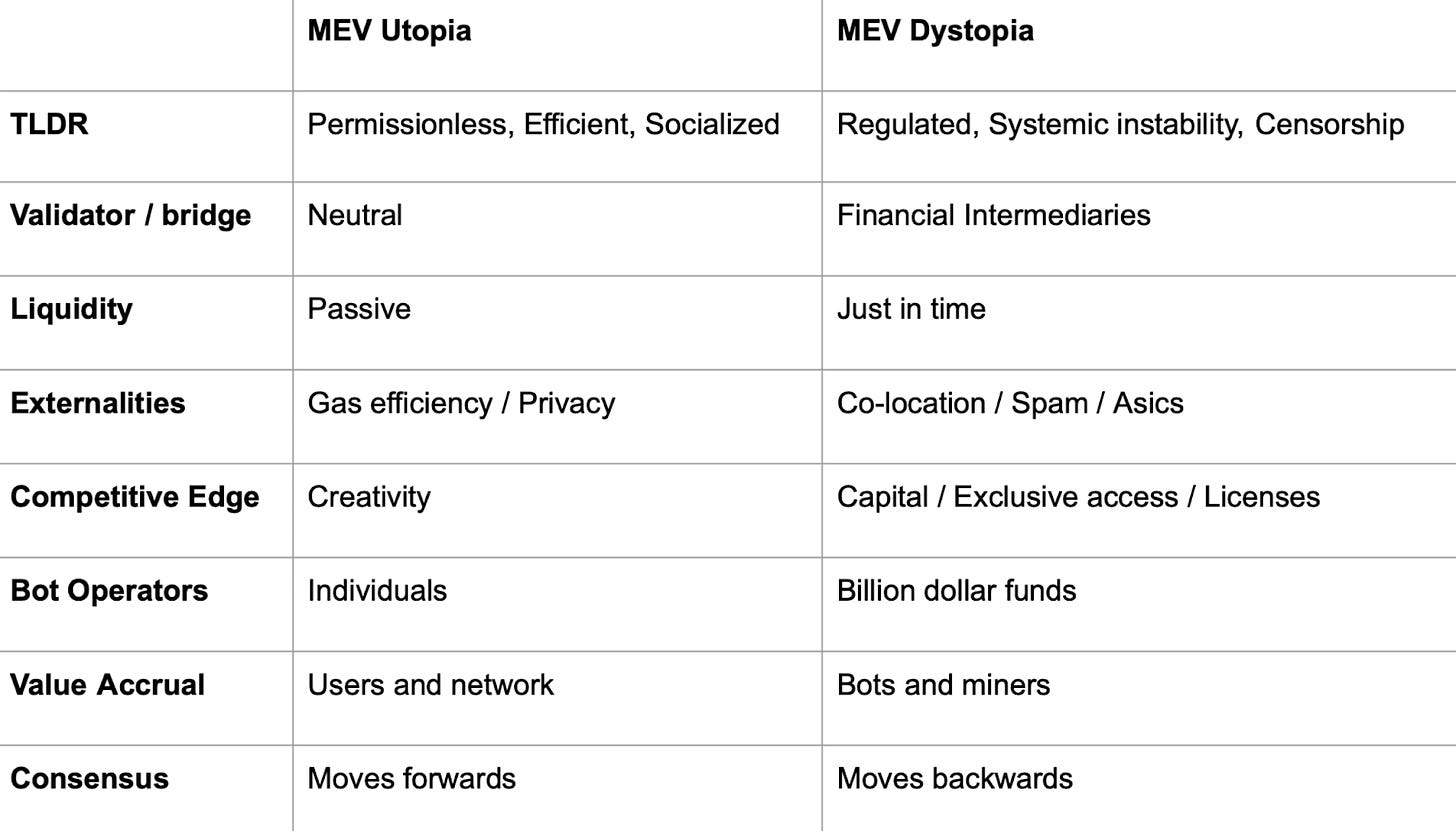

Utopia or Dystopia: Users as the Source of MEV

The MEV Supply Chain provides a useful framework for understanding the flow and extraction of value in blockchain ecosystems. It contrasts two potential futures: an MEV Utopia, where value generated by users is returned to them, and an MEV Dystopia, characterized by centralized block building and value capture by a few entities.

The dichotomy between Utopia and Dystopia is set within a capitalist framework, where the market's competitive forces determine the outcome. Utopia is envisioned as a fair return of value to users, while Dystopia involves centralization and monopolistic practices.

From a post-capitalist viewpoint, the focus should not merely be on the distribution of returns but on the systemic structures that empower people and enable equitable and sustainable value creation and self-governing distribution.

A major problem of the present MEV paradigm is the role that users play. Users are seen as sources of MEV, their intents and actions creating opportunities for value extraction. However, “users” are participants in an open source and collective system, not just sources of extractable value. The emphasis should be on empowering users to have greater control and decision-making power over how their intentions, actions and data are utilized within the blockchain ecosystem rather than what to do with their value once it is extracted. For example, one approach would be to implement MEV governance structures, perhaps decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), where users themselves decide how their value is used, distributing power and decision-making more equitably among participants rather than to market mechanisms or protocol design.

The Perceived Nature of MEV

Another major problem is that MEV is seen as a natural consequence of market dynamics in blockchain ecosystems. However, from a post-capitalist standpoint, the very concept of MEV could be reevaluated. Instead of accepting MEV as an inevitable aspect of blockchain markets, a post-capitalist approach might question how blockchain technologies could be reimagined to align with values like cooperation, mutual aid, equity and sustainability, rather than competitive extraction of value.

While these values are present in many open source and blockchain ecosystems, the profit motive, operating on the abstract notion that individuals are rational actors behaving self-interestedly, still reigns supreme. While people operate with many diverse motives, the MEV problem invites us to reimagine blockchain systems that are not just technically decentralized but are also socially equitable, ecologically sustainable, and directly-democratically governed, aligning technology with the values of Decentralized and Autonomous Societies more broadly.

MEV Exploitation: Mempools and Unethical Strategies

At the mempool level, MEV typically involves strategies known as “frontrunning”, “backrunning”, and “sandwich attacks”. Here's an example: Imagine a user submits a transaction to buy a large amount of a particular cryptocurrency. This transaction, while awaiting confirmation in the mempool, can be seen by miners or other participants with the technological capability to monitor mempool transactions. Anticipating that this large purchase will drive up the price of the cryptocurrency, these participants can buy it before the original transaction is confirmed, intending to sell it at a higher price immediately after.

Beyond frontrunning and arbitrage, other MEV strategies include:

Back Running: Profiting from trades that follow a significant transaction.

Sandwich Attacks: Placing orders before and after a large transaction to profit from market impact.

NFT Sniping: Using faster transactions to purchase NFTs as soon as they are listed at a lower price.

Additional strategies occur which exploit latencies between centralized and decentralized exchanges. In both centralized and decentralized exchanges, MEV can take the form of arbitrage opportunities. For instance, if a large trade on a decentralized exchange (DEX) creates a price discrepancy between DEXs and centralized exchanges, traders can exploit this difference before the market adjusts, realizing a profit from these temporary price differences.

The existence of centralized exchanges, coupled with arbitrage and latency games, mirrors the traditional financial system's exploitative practices. The pursuit of profit through these mechanisms perpetuates a narrative where wealth accumulates in the hands of a select few.

From a post-capitalist perspective, these MEV strategies and their countermeasures highlight several systemic issues:

Information Asymmetry: MEV thrives on unequal access to information, a fundamental contradiction to the ideals of transparency and fairness. It exemplifies how technological capabilities can be leveraged to create and exploit power imbalances.

Profit Motivation vs. Collective Good: The pursuit of MEV aligns with capitalist motivations of individual gain at the expense of collective network health. This self-interest undermines the communal ethos of blockchain technology.

Inequitable Access to Solutions: While initiatives to address these problems at the protocol level (like Danksharding and SUAVE discussed below) are commendable, their effectiveness may be limited to those with the resources and expertise to leverage them. This creates a barrier to entry, perpetuating the divide between the technologically elite and average users.

Shifting Focus to Collective Well-being: The emphasis on combating MEV should not only be on technological solutions but also on fostering a culture within the blockchain community that values the collective good over individual profit. This involves reimagining governance structures and incentive systems to prioritize equity, transparency, and communal welfare.

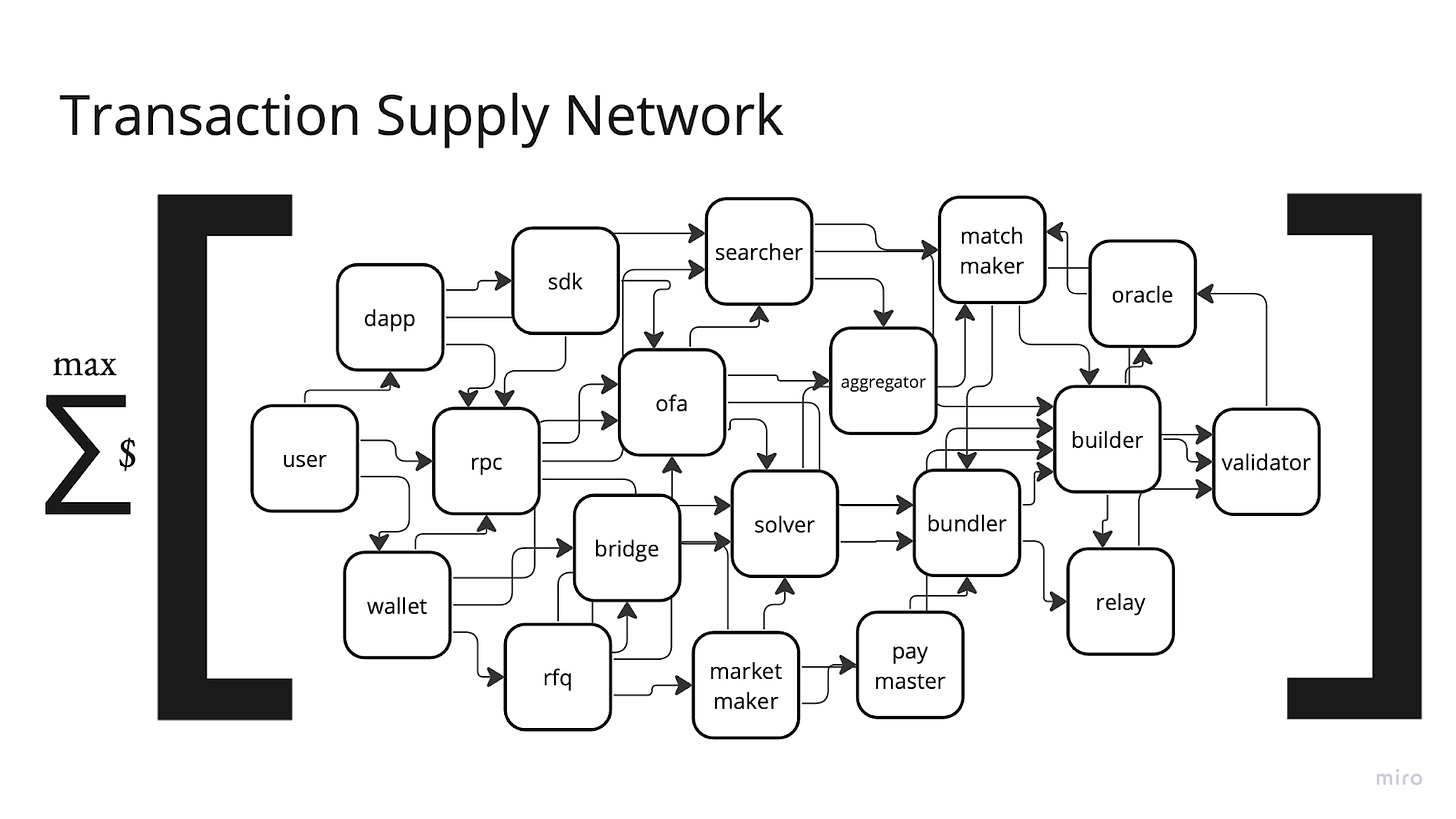

Tackling MEV Structurally: Proposer-Builder Separation, Proto-Danksharding (EIP-4844), Danksharding, SUAVE and MEV-Share

To address the problem of MEV management, a number of structural changes are being made to the core Ethereum protocol, and side chain modular solutions being developed, to produce different outcomes. These innovations, while not exhaustive, include “Proposer-Builder Separation”, “Proto-Danksharding”, “Danksharding”, “SUAVE” (Single Unifying Auctions for Value Expression) and MEV-Share. Let’s review these in turn.

Proposer-Builder Separation

Proposer-Builder Separation (PBS) introduces a fundamental change in blockchain transaction processing. This concept bifurcates the roles of block proposers and block builders. Traditionally, a single entity, typically miners or validators, would propose and construct blocks. However, under PBS, proposers are responsible for adding new blocks to the chain, while builders are tasked with assembling the content of these blocks. This separation is intended to decentralize power further within the blockchain network, addressing centralization concerns inherent in the block production process.

The implications of PBS for MEV are clear. PBS distributes responsibilities in block creation, reducing the concentration of power in the hands of a few entities and mitigating the risk of censorship or preferential treatment in transaction processing.

By separating the roles, PBS aims to create a more secure and fair environment for transaction processing. It ensures that the proposer, who adds the block to the blockchain, does not have undue influence over its content, thereby fostering a more equitable system.

Builders, specialized in assembling blocks, can optimize this process without the additional burden of maintaining network consensus. This specialization could lead to more efficient block construction and potentially reduce transaction costs for users.

PBS alters the dynamics of MEV extraction by distributing opportunities between proposers and builders. This can lead to a more balanced and transparent MEV market, where the benefits of MEV are more equitably distributed across different network participants.

Proto-Danksharding - EIP-4844

EIP-4844, known as Proto-Danksharding, proposes a significant step towards improving Ethereum's scalability. It aims to segment network data into smaller, manageable units known as “blobs,” thereby enhancing the efficiency of data handling and reducing transaction visibility in the mempool. This approach is expected to mitigate potential exploitations in MEV and lay the groundwork for the full implementation of Danksharding.

Danksharding

Building on Proto-Danksharding, Danksharding is envisioned as a comprehensive solution to Ethereum's scalability issues. It further optimizes data management, aiming to distribute network load more effectively. This structural change is crucial in addressing the centralization risks associated with MEV, ensuring more equitable transaction processing and enhancing the overall network performance.

SUAVE (Single Unifying Auctions for Value Expression)

SUAVE introduces a paradigm shift in transaction sequencing and block building. It decentralizes the process by unbundling the mempool and block builder roles from existing blockchains. SUAVE's architecture, comprising a Universal Preference Environment, Optimal Execution Market, and Decentralized Block Building, focuses on maximizing benefits for all stakeholders. The system aims to optimize revenue for validators, improve transaction execution for users, and maintain economic decentralization. SUAVE’s development emphasizes an open, collaborative approach, inviting diverse stakeholders to contribute to its evolution.

MEV-Share

MEV-Share represents an innovative approach to transaction processing on Ethereum. It facilitates the creation and execution of limit order bots, allowing users to execute trades when asset prices reach predetermined targets. Utilizing private order flow and advanced programming techniques, MEV-Share bots can monitor pending transactions that affect asset prices, enabling them to execute trades at favorable rates. These bots operate on the principle of backrunning - executing a trade immediately after a price-altering transaction. They are designed to ensure that orders are only filled at desired prices, with failed attempts incurring no transaction fees due to their execution via Flashbots. MEV-Share thus offers users a strategic edge in trading, combining elements of traditional limit orders with the advantages of private order flow and strategic transaction placement.

Post-Capitalist Critique

In a post-capitalist critique, while these technologies represent strides towards decentralization and efficiency, concerns remain:

Beyond Technical Decentralization: These solutions should ensure decentralization is not only technical but also translates into fair governance and community empowerment.

Economic and Power Dynamics: The need to address economic power imbalances is crucial, ensuring benefits are fairly distributed among all participants.

Collaboration Over Competition: These initiatives encourage cooperation, but mechanisms are needed to inherently promote collaborative behavior and mitigate competitive, profit-driven dynamics.

User Empowerment and Accessibility: Empowering users through technologies like MEV-Share is commendable. However, ensuring these tools are accessible and user-friendly for a broader audience is essential to prevent creating a divide between technically proficient users and others.

Risk of New Power Structures: In decentralizing block building and transaction processing, vigilance is needed to avoid establishing new forms of influence or control within the ecosystem.

Balancing Economic Incentives with Community Welfare: While maximizing revenue and transaction efficiency is important, these goals must be balanced against the broader welfare of the blockchain community and equitable value distribution.

Commitment to Openness and Decentralization: The commitment to openness and decentralization, as seen in initiatives like SUAVE, needs continuous reassessment to align with the evolving needs of the broader community and avoid perpetuating existing power structures.

In conclusion, the development of Proposer-Builder Separation and technologies like SUAVE, Proto-Danksharding, Danksharding, and MEV-Share represent significant advancements in addressing MEV and scalability challenges in blockchain technology. However, a post-capitalist critique emphasizes the necessity of a comprehensive approach that extends beyond technical solutions. This approach should include equitable governance, economic fairness, and genuine community empowerment, ensuring that the benefits of blockchain technology are widely and fairly distributed, aligned with broader societal and ecological goals. The ongoing evolution of these technologies presents an opportunity to reshape the blockchain landscape to foster a more equitable and sustainable digital future.

New Perspectives on MEV: Infinite Games

MEV must be reframed from a wealth redistribution problem to a wealth creation problem if we hope crypto to one day reach the promised land.

We should not be asking ourselves “how do we create a system that minimizes MEV” or “who should get the MEV”. We should be asking “how can MEV make crypto more useful” or “how can MEV be used to create better mechanisms”. - Frontier, Infinite Games

Frontier Research's "Infinite Games" essay represents some of the latest thinking around MEV, signaling future directions in the space. It frames MEV as a "new frontier," echoing the capitalist ethos of conquest and resource exploitation for profit. This view harks back to historical practices of territorial expansion. However, a more progressive perspective suggests viewing MEV as part of a shared digital ecosystem, emphasizing collective welfare and equitable resource distribution over individual gain.

MEV, characterized as an "infinite game," often implies an unending competition and value extraction cycle, mirroring the relentless drive of capitalist markets. In contrast, a post-capitalist approach advocates for sustainable, cooperative models focused on building resilient systems that support societal and environmental health over the long term. In short, breaking the cycle of endless competition.

However, this view requires going beyond markets. That is because the notion of "solving MEV", as akin to perfecting market mechanisms, reflects a traditional capitalist mindset. Instead of striving for mere efficiency, the focus should shift towards aligning these mechanisms with the principles of equity, sustainability, and community welfare. The objective is not to extract maximum value but to develop adaptable systems prioritizing human and ecological well-being.

Medieval Mappa Mundi: The Cartography of MEV

Frontier’s "Infinite Games" essay draws parallels between MEV and the Medieval Mappa Mundi, highlighting a desire for complete understanding and control of the crypto market, similar to early cartographic endeavors.

The Greek-French Philosopher Cornelius Castoriadis argued that modern Western ontology is based on the assumptions that society and history are driven by linear progress, perpetual growth and a drive to dominate nature. We believe these same assumptions are grafted onto the pursuit of endlessly solving and optimizing MEV.

Our critique outlined above challenges the notion of total comprehension and control, advocating for embracing complexity and uncertainty. It calls for decentralized, participatory decision-making processes and collective self-governance that incorporate diverse perspectives, countering the oversimplification risks of a singular, all-encompassing approach.

Final Thoughts

The emergence of MEV offers a window into the intricacies of blockchain protocols and crypto markets. It presents an opportunity not for relentless competition and value extraction but for cultivating cooperative, sustainable, and equitable economic systems aligned with the broader goals of Decentralized Autonomous Societies. This approach favors shared welfare, sustainability, and democratic participation over individual profit and market dominance.

Ultimately, addressing MEV in the blockchain space transcends technical challenges, demanding a philosophical shift from profit-driven individualism to an egalitarian, community-centric approach. Such a shift is vital for blockchain technology to fulfill its potential as an instrument of equitable and democratic systems.

delegat0x is a libertarian anti-capitalist R&D Engineer in the crypto space. They write about the intersections between philosophy, politics, media, alternatives to capitalism, social movements, and collective autonomy.

*In this article, we continue to refer to MEV even though Flashbots have updated their metrics naming convention from MEV to REV (for Realised Extractable Value), which they explain more accurately represents the actual realised and extracted amount, compared to a theoretical maximal amount.

Subscribe to delegate0x’s Substack

My personal Substack